Gay Pride: Part One

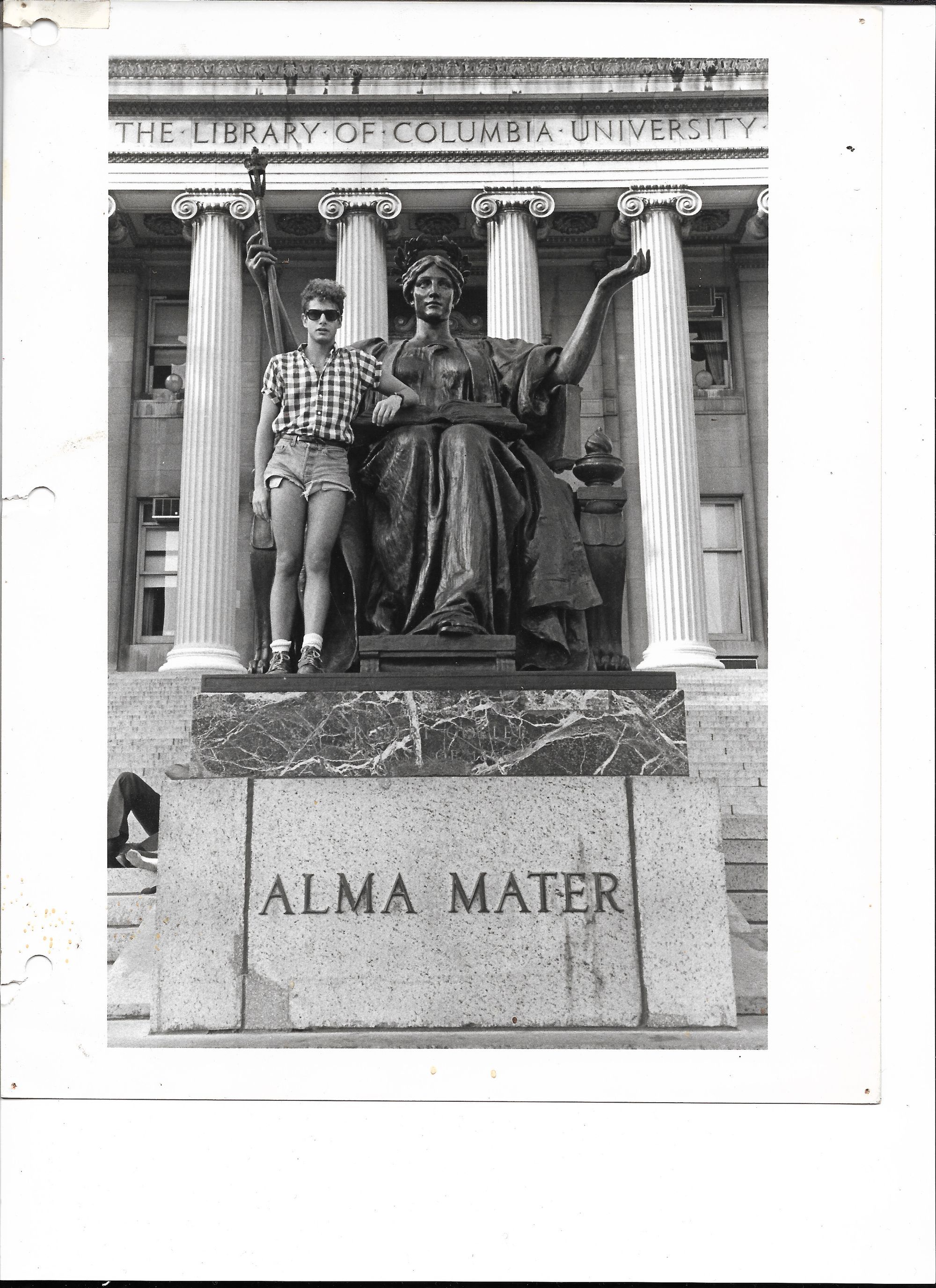

1977. The beginning of a gay pride story. My acceptance into Columbia College was ...

1977. The beginning of a gay pride story.

My acceptance into Columbia College was due to my mother’s witchery. Penny was adamant I break free from the Bronx’s limiting mentality that she feared would inhibit my intellectual potential, and she also insisted I accomplish this task while remaining under her care. I was, after all, der gracer—her first born—and she wasn’t going to let me slip away that easily.

She had to keep me close lest—god forbid!—her intuition be correct, and her eldest child be gay (very gay, I might add). I imagined her whispering secret, kabbalistic spells from the Old World to in a desperate attempt to procure for herself a future grandchild.

Getting into the Ivy League was a longshot, but we made the dream our “project.” I inherited from my mother a tendency to give my energy to the meeting the needs of others, a shared characteristic that made our work together particularly effective, if not fodder for future therapy.

Though my mother had not spent much time in college, herself, she had landed a career as a school secretary and wielded a decent executive skillset. Together, with an electric typewriter, Penny dictated a killer essay on the stoicism with which I, just shy of my Bar Mitzvah, suffered through four agonizing hip operations that opened my eyes to the fragility of life.

We reflected upon the exchange trip I took to Israel with thirty diverse NYC high schoolers. This gave way to a discourse on the importance of learning how to live with other races; despite my mother’s “fear of the other,” she believed it to be wrong to treat someone differently based on the color of their skin. There was humor in our essay, too: how funny that this “poor kid from the Bronx” has a love of opera, Shakespeare, and Bach! For good measure, we highlighted my impressive performance in the English section of the SATS, something worthy of note for not having had any preparation.

We got it, and in retrospect, it probably didn’t hurt that my admissions counselor was a gay man himself with a shared affinity for German philosopher (and proto-queer) Friedrich Nietzsche. Let’s just say, I had a good feeling after my interview.

I was in Israel when my parents informed me, via telegram, that I had been accepted. They were even more delighted by the fact I had also received a scholarship! It was my 18th birthday (April 20, 1977, for anyone wondering), and we were all shocked that I, a lower-middle class Bronx kid, got in.

Thrilled as I was to start my studies (I even read the “required reading,” Plato’s Republic, the summer before), I quickly realized that living at home in our “Co-Op City” apartment was not going to be sustainable.

We had four rooms, railroad-style, at 140 Alcott Place, which really meant: we had no privacy. There was never a dull moment. The apartment was hopelessly saturated in cigarette smoke and the heady “dope” from the glue my father used on his model airplanes glue. My mother, a die-hard democrat, had the news constantly playing on both the radio and the TV, which was occasionally drowned out by my brother practicing the drum and the idle chatter of friends and relatives on their daily visit.

There were no rails running from campus to Co-Op City (none had the courage), and more than once, I fell asleep on my way home, which took three trains and a bus one each direction. I got mugged once, which was perhaps less tragic than the time I left my researched AF paper (on Marx and Engels!) on the train, forcing my mother and I to stay up all night retyping the paper from scratch.

My first request to move on campus was a flat-out “no.” There was a housing shortage, and the Housing Dean had set a policy prohibiting any student who lived in the Boroughs from living in the dorms. So, Penny, ever my gutsy mother, went down to the Dean’s office and performed a sob story claiming I couldn’t live at home because my father was a raging alcoholic. While none of this was false (my father was a raging alcoholic), my mother’s tears worthy of an Academy Award. The tight-fisted Housing Dean gave in and secured for me a place at John Jay. Those crocodile tears were wiped off my mother’s face the moment she left the meeting.

Even as my life moved toward freedom, living at Columbia exposed me to a lot of the sick class shit from which I had been previously protected. The room I was assigned was tiny and, ironically, was shared with an alcoholic from New Jersey. This gave me the freedom to eat in the John Jay mess hall, where the tables were big, wooden, and shared with the elitist “Prep” clique.

Up until this point in my life, no one had taught me the fine art of cutlery. It wasn’t that we Bronx-bred ate like animals, it was just that holding both knife and fork at the same time and using the knife to scoop food onto the fork was something we didn’t do. To the Exeter boys, this was endlessly amusing, and they would laugh and grunt like apes as they mimicked my manner of eating. I became so humiliated that I once tossed a dining table over, thereby stripping me of my dining privileges and subjecting me to eating elsewhere, which I could not afford. I didn’t dare tell my parents.

To make a few extra bucks to buy food, I applied for a work-study position through the school. The only interview I was offered was for a position helping a sleep scientist from Harvard Medical School in organizing his dissertation for Stanford University.

And it was in the Bronx. So much for getting away!

It seemed crazy to me that, after finally leaving the Bronx for campus, I would have to return to my neighborhood just to pay for an expense incurred because of my Bronx upbringing and, to really send it home, work for a person I envisioned would be no better than the type of “slave master” knock-off already driving Bronx workers to become the raging alcoholics they were.

But I had no other choice.

On the day of my interview, I sat in the cafeteria of Monterfiore Hospital reading Nietzsche and drinking disgusting coffee to calm my nerves. At some point, I became aware that a gigantic man in a white doctor’s coat with flowing, hippie-style hair was glaring at me, and shortly thereafter, he stomped over to me, plopped his massive frame into a chair, and stared at me with an unnerving intensity. I found myself unable to pull my eyes away from his gaze. What the heck was going on?

Despite my secret forays to the porn theaters in Times Square (where I met up with wayward Puerto Rican youth in the booths they maintained), at that point in my life, I had yet to develop a “gaydar.” Thus, it did not occur to me then that this man might be, for some odd reason, attracted to me.

He was not conventionally handsome, but his Eastern European features, together with a pair of sharp brown eyes, and that long, black hair, bespoke a blazing intelligence that reminded me of Thoth, the Egyptian god of the arts and sciences.

Based on his gazelle-like grace, I could tell this man (who was at least six feet, four inches) was somewhat athletic.

I wanted him to go away so that I could continue reading, but what I managed to say was that I had "an interview for a stupid ass job, and that I read Nietzsche to calm my nerves." I had no idea what he found so funny, but he laughed very hard at this and asked me more about what I was reading.

So, I told him that Nietzsche was making me aware of the “slave consciousness" and its accompanying "resentment." I told him conformity was wrong and that it was especially wrong for me to work in a piece-of-shit hospital with some Ivy League sleep scientist who was undoubtedly going to exploit me. Despite all this, I told him, I was out of luck and hungry and too broke to even buy shit food, so I had to do something. For good measure, I mixed in some quotes from Nietzsche’s text, too.

Obviously, I had no idea that this white-coated, hairy giant was the man who was set to conduct my interview in approximately thirty minutes. He roared in laughter and cancelled the formal interview, telling me I was just the person he was looking for. I would start the next day.

For two years, I helped this 26-year-old scientist organize his articles on sleep research and corrected the of prose of his dissertation—I was, after all, an English major, studying under greats Edward Said, Edward Taylor, and Wallace Grey, may he Rest In Peace.

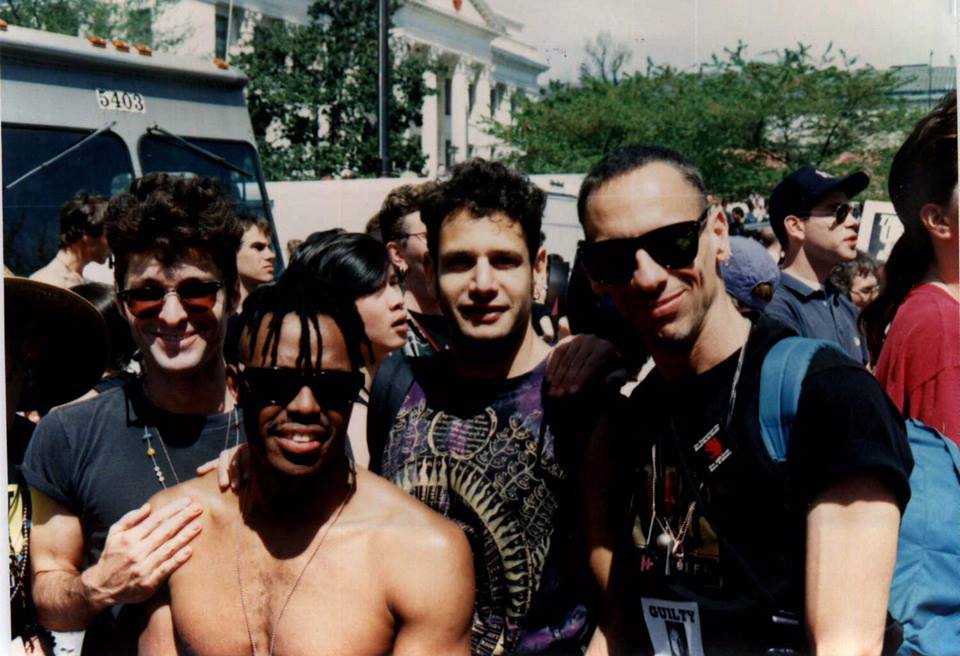

This work relationship evolved into a romantic love in which we both learned how to come out as gay, and I could write an entire book about the journey we had together. I loved him with my entire heart. He opened the world to me and, helped me become a man.

Sadly, I treated this man terribly for the five years we were together because I, still young and inexperienced, only knew how to exist in a relationship through moody manipulation rather than articulate my discontent in actual sentences. That skill would come only after years of analysis and personal work in breaking me of my bad habit, though to be honest, I still occasionally indulge in it to this day. I’m human, after all!

Flash forward to about a year ago, when I tried to make amends. When we met at an apartment near Melrose Avenue in Los Angeles, forty years had passed, and my first love had gotten married—to a woman.

While he did feel very much like the same man with whom I fell madly in love a lifetime ago, I felt he was also judging me for the less conformist and less opulent life he would have given me. We drank wine and reminisced about our trips to Paris and the time we actually lived together in the city of love for several months. Back then, we thought we’d be together for the rest of our lives.

But five years in, I broke his heart.

The good doctor would have taken care of me, but he was scientist, not a gay activist, and in the end, I had to find someone who could be more of a gay friend, teacher, and guide. I did find such a person, and I was able to become a gay artist standing on my own two feet.